Musical Relics of the Heluo Collection (Xia to Qing

Dynasty)

Zhao, J.

College of Music & Dance, Henan Normal University, Xinxiang 453000, China

Abstract: The focus of the musical relics of the Heluo collection (Xia to

Qing dynasty) is ??root culture?? in China. It looks at Heluo culture—an

important part of the Yellow River civilization—

and analyzes musical relics from the Heluo collection, which are stored at the

National Museum of China in Beijing, Henan Museum, Luoyang Museum, and several

archaeological institutes, in an attempt to research and classify the 102

relics dating from the Xia dynasty (2070-1600

BC) to the Qing dynasty (1636-1912 AD). The collection references the Heluo musical relics in

the Chinese Musical Relics Series:

Henan Volume (Zhonguo yinyue

wenwu daxi 2: Henan juan) and includes relevant content from works such

as Zhongzhou Opera Relics (Zhongzhou xiqu lishi wenwu) and Photographic Compendium of Chinese Opera Relics (Zhongguo xiqu wenwu tupu). The dataset

is archived in .doc format with the data size of 23.3 MB.

Keywords: Heluo region; musical relic; musical instrument; musical image;

Xia dynasty; Qing dynasty

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3974/geodp.2021.04.08

CSTR: https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.14.2021.04.08

Dataset Availability Statement:

The dataset supporting this paper was published and

is accessible through the Digital Journal

of Global Change Data Repository at:

https://doi.org/10.3974/geodb.2021.06.07.V1 or https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.11.2021.06.07.V1.

1 Introduction

The Heluo culture is an important part of Chinese

civilization. The term ??Heluo?? appears 108 times in twenty-five official dynastic histories (Ershiwu bu zheng shi), including 105 instances in the main text[1].

There are different opinions on the specific geographic boundaries of the Heluo

region. As for the regional scope of Heluo region, one definition refers to

Luoyang alone, and the other definition refers to Luoyang region, namely

Luoshui and Songshan area as the center, including the upper reaches of Rushui

and Yingshui, from Zhongtiaoshan in the north to Foniu Mountain in the south.

There is also a regional definition refers to the area where the Yellow River

and the Luo River meet. If the scope is slightly expanded, it will become a

synonym for almost the entire area of China known as the central plains.

Although scholars differ in their interpretations of the scope of the Heluo

region, Luoyang—the location of the ??root culture of the Chinese nation??—is

always at the heart of it, and it is the narrowest definition of the Heluo

region. For the purposes of this study, this narrow definition of the Heluo

region—Luoyang—as the scope of this musical relics collection and research was

used[2]. Luoyang is referred to as the ??cradle?? and

??foundation?? of Chinese and Eastern civilizations and was the heartland of the

Huaxia tribes and the Han nationality. It was home to the primitive Neolithic

cultures of the Peiligang, Yangshao, and Longshan cultures. It was also the

site of civilizations created by the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties and has

hosted a succession of cultural trends, including Lao-Zhuang Thought

(philosophies of Laozi and Zhuangzi), Confucianism, Mohism, Han scholasticism,

the metaphysical philosophies of the Wei and Jin dynasties, neo-Confucianism

and music culture, Buddhism, and Daoism. The music culture rooted in the Heluo

region was an important part of Heluo culture, and it gradually developed

toward unified diversity over time.

2 Metadata of the Dataset

The

metadata of Heluo musical relics dataset (Xia dynasty 2070 BC-Qing

dynasty 1912) is summarized in

Table 1. It includes the dataset full name, short name, authors, year of the

dataset, data format, data size, data publisher, and data sharing policy, etc.

Table 1 Metadata

summary of Heluo musical relics dataset (Xia dynasty 2070 BC-Qing dynasty 1912)

|

Items

|

Description

|

|

Dataset full name

|

Heluo musical relics dataset (Xia dynasty 2070 BC-Qing dynasty 1912)

|

|

Dataset

short name

|

HeluoMusicalRelics_Xia-Qing

|

|

Author

|

Zhao, J., College of Music

& Dance, Henan Normal University,719588683@qq.com

|

|

Geographical

region

|

Heluo

region (narrow sense), i.e. Luoyang

|

|

Year

|

Xia

dyansty (2070-1600

BC) to Qing dynasty (1636-1912 AD)

|

|

Data

format

|

.doc

|

|

|

|

Data

size

|

23.3

MB

|

|

|

|

Foundation

|

National Social Science Foundation

of China (19ZD16)

|

|

Data

publisher

|

Global

Change Research Data Publishing & Repository, http://www.geodoi.ac.cn

|

|

Address

|

No.

11A, Datun Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, China

|

|

Data

sharing policy

|

Data from

the Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository includes metadata, datasets

(in the Digital Journal of Global Change Data Repository), and

publications (in the Journal of Global Change Data & Discovery). Data sharing policy

includes: (1) Data are openly available and can be free downloaded via the

Internet; (2) End users are encouraged to use Data subject to

citation; (3) Users, who are by definition also value-added service

providers, are welcome to redistribute Data subject to written permission

from the GCdataPR Editorial Office and the issuance of a Data redistribution

license; and (4) If Data are used to compile new

datasets, the ??ten per cent principal?? should be followed such that Data

records utilized should not surpass 10% of the new dataset contents, while

sources should be clearly noted in suitable places in the new dataset[7]

|

|

Communication and searchable system

|

DOI,

CSTR, Crossref, DCI, CSCD, CNKI, SciEngine, WDS/ISC, GEOSS

|

3 Content and Cultural Features of the

Collection

3.1 The Relics in the

Collection

A full list of the Heluo musical relics, which span a very

long period, are presented below in Table 2.

It can be seen from Table 2 that the Heluo musical relics

have the following three main characteristics.

First, the relics cover a long period of continuous

history, from the Xia dynasty to the late Qing dynasty (though no relics have

been discovered from the Ming dynasty), providing material evidence of the

prolonged and unceasing development of music in the region.

Table 2 Heluo musical relics (information up to April

24, 2021)

|

Era

|

Relic

|

No.

of items

|

Type

|

Subtotal

|

|

Xia and Shang dynasties

|

Copper

bell

|

3

|

Percussion

instrument

|

5

|

|

Stone

chime

|

1

|

Percussion

instrument

|

|

Ceramic

Xun

|

1

|

Wind

instrument

|

|

Zhou dynasty

|

Western Zhou

|

Ceramic

Xun

|

1

|

Wind

instrument

|

7

|

|

Western Zhou

|

Set

of bells

|

1

|

Percussion

instrument

|

|

Spring and Autumn

|

Set

of chimes

|

1

|

Percussion

instrument

|

|

Eastern Zhou

|

Set

of chimes

|

1

|

Percussion

instrument

|

|

Warring States

|

Set

of large bells

|

1

|

Percussion

instrument

|

|

Warring States

|

Set

of bells

|

2

|

Percussion

instrument

|

|

Han dynasty

|

Music

and dance mural

|

1

|

Image

|

7

|

|

Musical

and dancing figurines

|

5

|

Image

|

|

Northern Wei dynasty

|

Musical

and dancing figurines

|

3

|

Image

|

18

|

|

Sarcophagus

musical image

|

2

|

Image

|

|

Grotto

musician image

|

11

|

Image

|

|

Northern Qi dynasty

|

Vessel

decoration

|

2

|

Image

|

2

|

|

Tang dynasty

|

Vessel

decoration

|

1

|

Image

|

33

|

|

Musical

figurines

|

6

|

Image

|

|

Musical

and dancing figurines

|

2

|

Image

|

|

Grotto

musician image

|

22

|

Image

|

|

Sanyue brick carving

|

1

|

Image

|

|

Song dynasty

|

Zaju opera brick carving

|

14

|

Image

|

15

|

|

Zaju opera brick carving

|

1

|

Image

|

|

Jin dynasty

|

Mandarin

duck pillow painting

|

1

|

Image

|

11

|

|

Sanyue and Zaju opera brick carving

|

6

|

Image

|

|

Sanyue brick carving

|

4

|

Image

|

|

Yuan dynasty

|

Music

and dance mural

|

1

|

Image

|

1

|

|

Qing dynasty

|

Guild

hall opera stage

|

2

|

Image

|

3

|

|

Script

|

1

|

Image

|

Second, the collection contains the highest achievements of

Chinese music culture from different historical periods, such as ceramic Xun (vessel flutes) (Figure 1), stone

chimes, and a copper bell (Figure 2) from the Erlitou culture (approximately

1900-1500 BC) discovered at Yanshi, Henan; sets of bells (Figure

3), chimes (Figure 4), and large bells (Figure 5) highlighting the cultural

achievements of the Zhou dynasty (1046-256 BC); music- and dance-related tomb figurines

and murals from the Han dynasty (202 BC-220 AD) (Figure 6); a musical image on a

sarcophagus and musical and dancing tomb figurines from the Northern and

Southern dynasties (386-589 AD) (Figure 7); frescoes and carved bricks

of Zaju opera from the Song (960-1279 AD) and Jin (1115-1234 AD) dynasties (Figure 8)[4]; and

a stage and scripts from the Yuan (1271-1368 AD), Ming (1368-1644 AD), and Qing (1636-1912 AD) dynasties (Figure 9)[5].

These are all tangible expressions of representative and popular artistic

styles from each period, and they fully exhibit the highest level of Chinese

music culture during the different eras.

Third, it confirms that Luoyang experienced severe ups and

downs in its long history. Beginning with the Xia dynasty, 105 emperors of 13

Chinese dynasties (Xia, Shang, Western Zhou, Eastern Zhou, Eastern Han, Cao

Wei, Western Jin, Northern Wei, Sui, Tang, Later Liang, Later Tang, and Later

Jin) established their capitals in Luoyang. Particularly from the Xia and Shang

dynasties to the Tang and Song dynasties, Luoyang was the center of the nation,

and its strategic location helped develop the region??s culture. The many

artefacts from the Xia and Shang to the Song and Jin dynasties excavated at

Luoyang are a powerful testament to the city??s extraordinary cultural and

artistic value. The transfer of many functions away from Luoyang starting in

the Southern Song dynasty and lasting until the end of the Qing dynasty,

however, affected the city??s cultural development considerably. The musical

relics in this collection powerfully confirm the changing role and status of

Luoyang in Chinese history. As such, the history and features of music culture

represented in this collection also encapsulate the historical development of

the Heluo region.

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 1 Erlitou ceramic Xun Yanshi, Luoyan

|

Figure 2 Erlitou copper bell, Yanshi, Luoyang

|

Figure 3 Set of bells from Warring States period

discovered at Jiefang Road, Luoyang

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure

4 Set of chimes from

Spring and Autumn period discovered at Zhongzhou Road, Luoyang

|

Figure 5 Set of large bells from Eastern Zhou

discovered at

Jiefang Road, Luoyang

|

Figure 6 Music and dance tomb figurines from

Eastern Han found in Miaonan new village, Luoyang

|

|

|

|

|

|

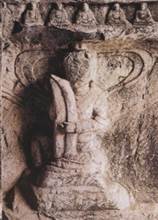

Figure

7 Musical image

on a sarcophagus from Northern Wei excavated at Luoyang

|

Figure 8 Zaju

opera carved bricks from the Song dynasty discovered at Luoyang

|

Figure 9 Qing dynasty guild hall opera stage in

Luoyang

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.2

Cultural Features Reflected in the Musical Relics

The collections reflect the achievements of Chinese culture

in the field of music during different historical periods, which can be seen in

the following six aspects.

(1) Pre-Qin rites and music culture

The system of rites and music can be

traced back to the Xia (2070–1600 BC) and Shang (1600–1046 BC) dynasties and

were established by the Western Zhou dynasty (1045–771 BC). Impressive aspects

of pre-Qin culture, especially Zhou culture, were enhanced by the establishment

of this important system, which are one of the earliest indicators in China and

evidence of the establishment of a political system and social norms. Elements

consistent with this culture have been identified in the collection of musical

relics from the Heluo region.

In 1024 BC, early in the Western Zhou dynasty, the Duke of

Zhou was ordered to build Luoyang, and it served as the eastern capital of the

Western Zhou dynasty and the capital of the Eastern Zhou dynasty until the Zhou

dynasty was overthrown twice by the Qin dynasty, once in 256 BC and again in

244 BC. The important instruments connected to the rites and music system from

the Western Zhou dynasty which have been excavated at Luoyang, including a set

of bells discovered in Xigong district, chimes discovered at Jiefang road, and

bells discovered at Tomb 131 in Luoyang, are all strong proof of the prosperity

and development of a bronze rites and music culture at that time as well as the

cultural achievements and heights it produced[6]. This kind

of culture is an important representation of the heights reached by Chinese

culture in the pre-Qin period, and the continuous development of this culture

after the Zhou dynasty evolved into laws, folk customs, and morality and

ideology, so it played an foundational role in the culture of the Chinese

nation.

(2) Han dynasty music and dance culture

In the Han dynasty (202 BC–220 AD), culture and art

developed and prospered. This was partly thanks to the establishment of a

government office responsible for collecting folk songs, but most importantly

to the traditional customs and ceremonies of ordinary people. Many new concepts

and terms appear in records from the Han dynasty, for example, baixi, which is a general term for

performances such as music, acrobatics, illusion, and martial arts, which

reflects the development trend in people??s interests and ideas that formed Han

culture. Of the cultural relics discovered in the Heluo region, murals, carved

portrait bricks, and musical and dancing tomb figurines are important items

that allude to these new trends. These include the music and dance mural found

in a tomb at Yuxin village, Luoyang (Figure 10), a portrait brick of women

dancing discovered in Yichuan county, Luoyang (Figure 11), and plate and drum

dance (Panguwu) tomb figurines

discovered at Qilihe in Luoyang (Figure 12)[4]. They not only

represent the height of music culture but also people??s concepts regarding

death and the development of tomb culture.

(3) Cultures of the six dynasties and tomb culture

The Six dynasties period (222–589 AD) was notable for the

frequency of wars and degree of social turbulence. Despite constantly

alternating between periods of prosperity and decline for more than three

centuries, there was diverse political, economic, and cultural development.

This can be seen in the development of Buddhism, evidenced by the discovery of

music-related cave statues found in Buddhist grottoes in Heluo, including

various flying musician statues discovered at the Longmen Grottoes dating from

the Northern Wei. In addition, the sustained development of tomb culture is

reflected in the magnificent portrait bricks, portrait stones, and musician

figurines from that era (Figure 13)[6].

(4) Music and dance culture and Buddhist culture during the

Sui dynasty, Tang dynasty, and Five dynasties

During the Sui (581–618 AD) and Tang dynasty (618–907 AD),

which was considered a golden age of Chinese feudal society, as well as during

the turbulent Five dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–979 AD), the Heluo

region, and especially Luoyang, remained the center that drove China??s

development. The number and quality of musical relics and Buddhist statues

discovered in this region directly reflect characteristics of the music. These

include painted musical and dancing figurines unearthed from a tomb of the Cen

family in Mengjin, Luoyang (Figure 14); musical and dancing figurines found at

Xu village, Luoyang; horse-riding musical figurines unearthed from the tomb of

Liu, Kai in Yanshi, Luoyang; and the musical statues preserved in caves at

Longmen Grottoes, including the cave of ten thousand buddhas, Gushang cave,

Bazuoci Buddhist altar, Longhua-Si cave, Fengnan cave, Huoshao caves, Gunan

cave, Jinan cave, and Zhao Keshi cave (Figure 15)[4].

(5) Folk music culture during the Song and Jin dynasties

The Song (960–1279 AD) and Jin (1115–1234 AD) dynasties

constituted an important stage in the transition of Chinese culture from the

middle ages to the modern age. The prosperity of folk culture represented by

urban culture provided a cultural field and opportunity for the development of

music. It led to the emergence and popularity of Zaju opera, Zhugongdiao (a style of song

prevalent in the 11th century), Changzhuan (a form of entertainment consisting of talking and

singing), Guzici (a form of

spoken art accompanied by a drumbeat), and Jin Zaju opera. Musical relics excavated in the Heluo region

strongly evidence these changes. Unearthed relics include carved bricks

featuring Zaju motifs found at

Jiuliugou in Luoyang (Figure 16)[4] and at Luoningjie village in

Luoyang, Sanyue carved bricks

found in a Jin dynasty tomb on Daobei road in Luoyang, a portrait on a

sarcophagus found in Menjin county in Luoyang, and a colorful Jin dynasty

pillow.

|

|

|

|

|

Figure

10 Music and

dance mural found in a tomb at Yuxin village, Luoyang

|

Figure

11 Portrait

brick of women dancing discovered

in Yichuan

county, Luoyang

|

Figure

12 Plate and

drum dance (Panguwu) tomb

figurines discovered at Qilihe in Luoyang

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 13 Musician figurines dating to the

Northern Wei dynasty discovered in Yuan Shao??s tomb in the Old Town district

of Luoyang

|

Figure

14 Musical figurine

unearthed from a tomb of the Cen family in Mengjin,

Luoyang

|

Figure

15 Statue of a

musician playing a konghou in

the Cave of Ten Thousand Buddhas at Longmen Grottoes

|

(6) Ming and Qing dynasties opera art

|

Figure 16 Carved bricks featuring Zaju motifs found at Jiuliugou

|

Following on from the development of Zaju opera during the Song, Jin, and

Yuan dynasties, opera as an artform enjoyed a golden age of development during

the Ming and Qing dynasties. This was driven by the rapid expansion of a

commodity economy, as well as by the accumulation of various musical styles and

diversified exchanges in the previous period, and by cooperation between

scholars and musical performers. Although opera performances from that time

have not been preserved in their original formats, some physical cultural

relics of opera performances powerfully testify to the popularity of the

artform. The Heluo region is no exception to this, which is home to the Luze

Huiguan Dancehall (Figure 9)[5], Shanshan Huiguan Dancehall, and

Guanlin Dancehall.

3.3 Analysis of Musical

Relics in the Collection

The Heluo relics contain a wealth of musical information,

including the following.

(1) Symbols of music culture

The musical relics in the collection reflect styles of

music during different periods. The relics can be divided into two categories:

precious musical instrument relics and vivid image relics. These are the two

main and most important forms of musical relics currently availables. Musical

instruments have the characteristics of being authentic and directly

perceptible. They allow people to directly observe and analyze their structure

and sound to determine the pitch, interval, and tone of the actual instruments

for a deeper understanding of their musicological characteristics. There are

also drawbacks to these cultural vessels, including separation from the context

in which they would have been used. To an extent, this limits our ability to

interpret their cultural functions and other characteristics.

The advantages and disadvantages of image-based cultural

relics are exactly the opposite of those of tangible musical instruments.

Image-based relics are physical materials that indirectly reflect musical

characteristics. Their advantage lies in their presentation of the occasions

and cultural functions associated with musical instruments. However, their

virtual and freehand nature limit our understanding of their specific

characteristics. Images of musical instruments, music and dance scenes, and

opera from the Qin and Han dynasties and later eras prominently depict the

methods and functions of music, which have become an starting point for people

today to interpret related issues in different historical periods.

(2) The development path of music culture

There are inherited and characteristics of musical relics

in this collection, including among types of musical instruments, music and

dance, and opera. Taking physical musical relics as an example, the musical

instruments of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties have inherited similarities,

but they also reflect significant developments and changes, evidenced by the

types, forms, and quantities of musical relics that have been excavated.

First, the musical instruments discovered from the Xia,

Shang, and Zhou dynasties are all wind and percussion instruments. Only one

type of wind instrument has been found from any era: ceramic Xun (vessel flute) in our defined

area of Heluo. However, its inherited features are very significant. Only two

types of percussion instrument from the Xia and Shang periods have been

discovered: copper bells and stone chimes, but many new types of percussion

instruments appeared during the Zhou dynasty, such as sets of stone chimes, and

sets of tuned bells. It is clear that the stone chimes used as melodic

instruments in the Zhou dynasty were a development of the single chime used as

a rhythmical instrument during Xia and Shang times. The advances not only

reflect improvements in accuracy of pitch, but also a greater desire and

ability to control pitch intervals. The chime instruments were developed from

the bronze bell instruments used during the Xia and Shang periods, greatly

surpassing them in terms of their production process and in the stability and

richness of their musical sound. During the Warring States period, the people

in Heluo developed sets of large bells based on those produced in the south.

This not only illustrates the process and result of cultural exchanges, but

also shows the popularity of such instruments in the north, which led to

corresponding advancements.

Second, there are obvious changes in the shapes and

structures of similar musical instruments in different periods. Taking ceramic Xun as an example, during the Xia and

Shang dynasties, they tended to only have one blow hole and two sound holes[8].

Sound tests have shown that they could only play two tones. The Xun from the Western Zhou dynasty,

however, have one blow hole and five sound holes and can play at least six

tones (Figure 17), which greatly improved its performance as well as the

richness and artistic expressiveness of the melody that could be played on the

instrument[4].

Finally, considerably more musical instruments—both

percussion and wind—have been excavated that date to the Zhou dynasty than date

to the Xia and Shang dynasties. This indicates increasing demand for music and

culture during the Zhou dynasty, and it suggests that musical life became

richer and more diverse during the Zhou dynasty.

(3) Distinctive characteristics of musical instruments from

different periods

Of the musical relics in this collection, the most abundant

are from the Tang dynasty. These are of four types: decorated vessels, musical

and dancing figurines, musician carvings from grottoes, and Sanyue carved bricks. There is only

one type of relic from each of the Northern Qi and Yuan dynasties: decorated

vessels and music and dance murals, respectively. To a certain extent, this

reflects the different methods of representing, and differences in the cultural

function of music in different periods.

|

Figure

17 Ceramic Xun from the Western Zhou discovered at Jiwa Factory in Luoyang

|

Figure 18 Carving of a Pipa player at Longmen Grottoes, Luoyang

|

Figure 19 Carving of a person beating drums with

sticks at Longmen Grottoes, Luoyang

|

The Tang dynasty was a period of development known for its

extensive multi-ethnic cultural exchanges, unprecedented prosperity, and

thriving politics. Its significant cultural prosperity provided the conditions

for the thriving development of music culture. Outstanding artistic

achievements from that time are embodied in tunes representing popular folk

music, palace entertainment representing the cultural achievements of court

music, and the grotto statues representing features of Buddhist music culture.

It can be seen from the Tang dynasty musical relics that have been collected

and sorted that, of the aforementioned four types of relics, the grotto carved

musical figures are greatest in number (22), which highlights the importance

Buddhism attached to music during its dissemination in China. It also reflects

the great emphasis Tang dynasty rulers placed on Buddhism and Buddhist music

(Figures 18, 19)[4]. It served as a special medium for the exchange

of Chinese traditional music and music culture along the Silk Road and provided

the conditions for the diverse absorption and development of traditional

Chinese music.

(4) The artistic value of the musical relics

The Zaju-themed carved bricks discovered in the Yanshi

district of Luoyang dating to the Song dynasty are a prime example of the

artistic value of the items in the collection. Zaju opera was a development of the song and dance plays popular

during the Northern and Southern dynasties period and of Tang dynasty plays. In

April 1958, a cultural relics team from the Henan Provincial Department of

Culture conducted an excavation of a collapsed tomb on the west bank of

Jiuliugou Reservoir in Yanshi, where they discovered six carved portrait

bricks. One group of three carved bricks depicts a maidservant, and the other

group of three bricks depicts a Zaju

opera performer[5]. The Zaju

bricks include one figure on one brick and two figures on each of the other two

bricks. The brick engraved with the single figure shows a man wearing a

headscarf and a round-necked robe with a belt around his waist. He is holding a

vertical painting and is leaning slightly, as if explaining something to

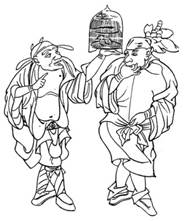

someone (Figure 20)[9]. One of the carved bricks containing two

figures shows one person wearing a headscarf and the other a Dongpo hat (Figure

21)[9]. On the final Zaju-themed

brick, one of the figures is holding a birdcage while the other is using his

fingers to whistle. Both figures are wearing soft cloth headscarves (Figure 22)[9].

This set of delicately

carved bricks depict elements of Zaju

opera during the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127 AD) as well as characteristics

of Chinese opera in its early stages of maturity, which can be seen in the

carved bricks excavated at Yanshi and in the Zaju carved bricks discovered at the Song tombs at Baisha

located in Yuzhou, Henan province, only 120 km from Yanshi. These features were

initially developed by Canjun

opera during the Tang dynasty. This set of musical relics provides strong

evidence that northwestern Henan was an important region for musical

development during the Song dynasty and the birthplace of Zaju opera, as described in

historical documents. There are many examples of similar musical relics in this

collection.

|

Figure 20 Zaju-themed brick carving from Song

dynasty found at Yanshi, Luoyang

|

Figure 21 Zaju-themed brick carving from Song

dynasty found at Yanshi, Luoyang

|

Figure 22 Zaju-themed brick carving from Song

dynasty found at Yanshi, Luoyang

|

4 Conclusion

This study looked at musical relics in the collection of

Luoyang Museum excavated within the city of Luoyang. The historical content,

cultural composition, and musical elements of the relics were analyzed to

reveal the typical features, academic value, and cultural roots of the region??s

musical culture. These musical relics are vital and irreplaceable for

understanding Heluo culture, the Yellow River civilization, and Chinese

traditional culture.

Conflicts

of Interest

The

authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

[1]

Cheng, Y.

W. An Introduction to Heluo Culture (Heluo Wenhua Gailun) [M]. Zhengzhou:

Henan People??s Publishing House, 2007: 2.

[2]

Xue, R. Z.,

Xu, Z. Y. Supplements and corrections to research on ??Heluo?? and the ??Heluo

Region?? [J], Journal of Chinese Historical Geography, 1999, 2: 217-225.

[3]

Zhao, J.

Heluo musical relics collection (Xia dynasty–Qing dynasty) [J/DB/OL]. Digital Journal of Global Change Data

Repository, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3974/geodb.2021.06.07.V1. https://cstr.escience.org.cn/

CSTR:20146.11.2021.06.07.V1.

[4]

GCdataPR

Editorial Office. GCdataPR data sharing policy [OL].

https://doi.org/10.3974/dp.policy.2014.05 (Updated 2017).

[5]

Music

Research Institute of China Academy of Art, Henan Institute of Archaeology, Henan

Museum. Chinese Musical Relics: Henan

Volume [M]. Zhengzhou: Elephant press, 1996.

[6]

Liao, B.,

Zhao, J. X. Photographic Compendium of

Chinese Opera Relics [M]. Beijing: China Drama Publishing House, 2015:

51.

[7]

Sun, M.,

Wang, L. F. The History of Luoyang??s

Ancient Music Culture: a Record of the History of Luoyang??s Ancient Music

Culture [M]. Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House, 2004.

[8]

Yang, H. Z.

Zhou dynasty Rites and Music and Heluo

Culture [M]. Zhengzhou: Henan People??s Publishing House, 2018.

[9]

Excavation

Team of the Institute of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Brief report on

the excavation of the Erlitou Site in Yanshi, Luoyang, Henan [J]. Acta

Archaeologica Sinica, 1965, 5: 215–229.

[10]

Xu, P. F. Collection of Xu Pingfang??s Works on Chinese

History and Archaeology [M]. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books

Publishing House, 2012: 253.