The Spatial Dataset of 2555 Chinese Traditional Villages

Yu, L.1* Liu, J.2 Ding, Y. Q.1 Cao, Q. Y.1 Liao, Q. X.1 Tang, M. J.1 Fu, M.1

1. School of Architecture, Soochow University, Suzhou 215123, China;

2. Institute of Agricultural Resources and Regional Planning, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences,

Beijing 100081, China

Abstract: The spatial dataset introduced in this data paper included attributes and spatial information of 2,555 Chinese traditional villages. Its attribute information consists of village names and their administrative affiliations (provincial-prefectural-county-township), mainly from three published lists of Chinese traditional villages by Chinese government during 2012-2014. Its geographical information was mainly developed based on Baidu map and Google Earth images, and aided by historical documentations to better determine some villages’ geographical location. In a few cases where the village was found neither on the Baidu map nor on the Google Earth image, the information from the upper level administrative (township) nearby was adopted for a proxy. The dataset was archived in .shp and .kmz formats with data size of 6.88 MB in 8 files (Compressed to 416 KB in 2 files). The analysis paper was published at the journal of Progress in Geography, Vol. 35, No.11, 2016.

Keywords: China; traditional village; spatial distribution; progress in geography

1 Introduction

Traditional village, a form of aggregation of rural residences and buildings in space, is spread all over the country. The living spaces are adapted to local conditions, grow in its way and present in a variety of architectural forms, which have distinct regional characteristics (Figure 1)[1]. As the valuable historical and cultural heritage, the traditional villages (except for the necessary narratives, omitting the “traditional” below) reflect the record of the real simple folk customs and lifestyles, and the abundant forms are not only influenced by factors such as economic, culture and traditional concepts at that time, but also affected by natural factors like topography and landform[2], analytical research not only needs to rely on a large number of effective micro-data, but also should strengthen the villages spatial distribution in macro-level. There have been many similar studies on village distribution[3–5]. The spatial distribution dataset of 2,555 traditional villages in China is a basic data for analyzing and interpreting the geographical features, spatial development and layout of villages. In the analytical papers about this dataset, the hierarchical method of geographic grid is also applied, which forms a convenient and unified frame-work for data grading and the integration of multivariate data[6–7]. Due to the convenience of analysis and comparison of spatial data and visual expression, geographical grid system has been widely used[8–9].

Figure 1 Traditional villages with distinctive regional characteristics (Left: Shuiyu village, Nanjiaoxiang, Fangshan, Beijing[10]; Right: Liruo village, Shitang, Wenling, Taizhou[11])

2 Metadata of Dataset

The metadata of the spatial distribution dataset of 2555 Chinese traditional Villages[12] is summarized in Table 1. It includes the full name, authors, data format, data size, data files, data publisher, and data sharing policy, etc.

Table 1 Metadata summary of the spatial dataset of 2555 Chinese traditional villages

|

Items

|

Description

|

|

Dataset full name

|

The spatial distribution dataset of 2555 Chinese traditional villages

|

|

Dataset short name

|

VillagesChina2555

|

|

Authors

|

Yu, L. F-8099-2018, School of Architecture, Soochow University, yuliang_163cn@163.com

Liu, J. O-6279-2018, Institute of Agricultural Resources and Regional Planning, liujia06@caas.cn

Cao, Q. Y. O-6478-2018, School of Architecture, Soochow University, 604459330@qq.com

Ding, Y. Q. O-6445-2018, School of Architecture, Soochow University, 442801422@qq.com

Liao, Q. X. O-6442-2018, School of Architecture, Soochow University, 719197729@qq.com

Tang, M. J. O-6467-2018, School of Architecture, Soochow University, 361988267@qq.com

Fu, M. O-6455-2018, School of Architecture, Soochow University, 821064405@qq.com

|

|

Geographical region

|

China, 31 provincial-level administrative regions (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan)

|

|

Year

|

2012-2014

|

|

Data format

|

.shp, .kmz

|

|

|

|

Data size

|

6.88 MB

|

|

|

|

Data files

|

two files (VillagesChina2555.kmz, VillagesChina2555.rar)

|

|

Foundation(s)

|

National Natural Science Foundation of China (41371173)

|

|

Data publisher

|

Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository, http://www.geodoi.ac.cn

|

|

Address

|

No. 11A, Datun Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, China

|

|

Data sharing policy

|

Data from the Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository includes metadata, datasets (data products), and publications (in this case, in the Journal of Global Change Data & Discovery). Data sharing policy includes: (1) Data are openly available and can be free downloaded via the Internet; (2) End users are encouraged to use Data subject to citation; (3) Users, who are by definition also value-added service providers, are welcome to redistribute Data subject to written permission from the GCdataPR Editorial Office and the issuance of a Data redistribution license; and (4) If Data are used to compile new datasets, the ‘ten percent principal’ should be followed such that Data records utilized should not surpass 10% of the new dataset contents, while sources should be clearly noted in suitable places in the new dataset[13]

|

3 Methods

Data is the basis of research, but the published village lists have no geographical location, and some villages’ names are not clear, therefore, it is necessary to identify the villages’ names and relate each village name to a geographic coordinate system. Due to the space of shelter and isolation from the outside world, it can be considered that villages are the collection and natural carrier of folk dwellings (Figure 2). The geographical information of a village was mainly extracted from identification of the village name and the characteristics of the residential structure of the village space, based on village name and residence pattern, the administrative affiliations of a village was determined by official documents (Provincial-Prefectural-County-Township).

Figure 2 Folk dwelling in village and dwelling and Village interdependence (Left: Shuiyu village,

Nanjiao town, Fangshan, Beijing; Right: Liruo village, Shitang town, Wenling city, Taizhou city.

Photographed by the Yu, L.)

3.1 Study Area

Dataset: China, covering 31 provincial administrative regions (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan).Village raw data: Three batches of the list of national traditional villages in China released by the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of P. R. China, Ministry of Culture of P. R. China, and Ministry of Finance of P. R. China since 2012 (the first batch of 646, the second batch of 915 and the third batch of 994, excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan regions, with no coordinates). Taking the 2,555 villages in the three batches of the list as the objects, the dataset was to assign geographical coordinates and confirm administrative affiliation of the villages to form the spatial point data of villages.

3.2 Development of Geographical Information

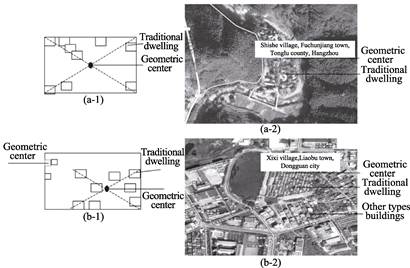

Folk house is an important factor of space composition and the basis of image interpretation. The positional relationship of the village is judged and paired according to the village coordinates and its accompanying text information. The village point data extracted from the Baidu map[6] were overlaid to Google Earth Imagery for cross-checking and fine-tuning (Figure 3). Then, a .kmz file was produced and further converted to a .shp format file.

At first, the village point data extracted by Baidu map is composed of geographic coordinates and image data. The number of dwellings in village was more than one thousand and the roofs were planar distribution in images. Therefore, the geometric center of the village in the image was regarded as the village’s coordinate. In addition, Google images of relevant locations were captured as supplements to aid visual inspection. The following three criteria

Figure 3 Fine-tuning the location of the village based on Google Earth image (Shuiyu village, Nanfang township, Fangshan district, Beijing)

were also considered when extracting:

(1) Get the village coordinate information directly from the text of the map, without image assistance.

(2) Get clear remote sensing images of villages from the map, and obtain coordinates by judging the geometric centers of villages, which are easy to generate the following two situations:

?? For small regular villages, the extracted plane geometric center is used as the village coordinates. Figure 4(a-1), 4(a-2) shows the extraction judgment process of Shishe village, Fuchunjiang rown, Tonglu county, Hangzhou city.

?? For large villages, especially for villages with complex houses established in various historical periods, the coordinates are placed on the geometric center of ancient and unified buildings. The shape of the residential dwellings in a certain space would be relatively unified and coordinated due to the influence of technical conditions at that time. Figure 4(b-1), 4(b-2) shows the extraction process of Xixi village, Liaobu town, Dongguan city.

Figure 4 Schematic diagram of coordinate selection

(3) If it is difficult to find the coordinate information of the village on the map, and there is no reference remote sensing image, take the coordinate of the administrative units at the upper level where the village is located as the geographical coordinate of the village.

The village coordinate data extracted according to the above methods is shown in Table 2. It can be seen that in the first, second and third groups of traditional villages, the number of villages whose coordinates were directly collected from map and images or taken from the geometric center accounted for 79%, 64%, and 82% of the total number of villages published in three batches, respectively. The number of villages whose coordinate was replaced by the higher authorities’ coordinates accounted for 21%, 36%, and 18%, respectively, and the average value of the three batches was about 25%, which was relatively small. It can be considered that the impact on the overall results of the study is limited.

Table 2 Coordinate statistics of three batches of traditional villages

|

Batch and type

|

Replaced by superior coordinates

|

Directly use real coordinates

|

Use geometric center coordinates

|

|

First batch

|

134

|

464

|

48

|

|

Second batch

|

332

|

519

|

64

|

|

Third batch

|

177

|

799

|

18

|

3.3 Development of Attributive Information

The original published village names expressed by text were unstructured—one village one line, using a series of texts which could basically distinguish the village and its administrative affiliation. Theoretically, it seems simple to organize these texts in the administrative hierarchy to an attributive table. Such as in the first row of traditional village of the first batch: Shuiyu village, Nanxun town, Fangshan district, Beijing. There is a township or the administrative mark of the town after omitting the prepositive districts and counties, and there were clear four levels above village: provincial, prefectural, county, and township.

However, in practice, the development of attributive information was complex. On the one hand, not all villages were named following the rigid naming convention; on the other hand, there were confusions in the 4-level administrative hierarchy. Several typical phenomena are listed below:

(1) Administrative level upgrading: before the reform and opening to the outside part, county-level units were clearly marked “county”, but now there are quite a few places called county-level cities. It is difficult to determine its level due to the suffix “city”. For instance, the “Longquan city” in the “Longnan township, Longquan city, Lishui city”, although it is called the city, but it is actually a “county”, so it belongs to the “county” section.

(2) The functions of some naming were unclear: like the “suburb” in the “Xiaohe village, Yijing town, suburb of Yangquan city”. Generally “suburb” refers to the immediate vicinity of the central city which the geographical scope of providing agricultural and sideline products to cities mainly during the planned economy period, both functional positioning and name. However, this column needs to have an independent name, but it is in the “county” section because there is no county name.

(3) Although the end of the name was mostly marked by the village, some were also the name of the group, village committee, or fort, etc. These are “village” or subordinate organization, and even alias, which is at the end of the mark and was marked as the “village level”. If the end of the indication was unclear, it will be confirmed by further search and inspection.

4 Results and Validation

4.1 Data Composition

The dataset consists of 2 subsets, which respectively are the .shp version of ArcGis and. kmz version of Google of the spatial distribution data of 2,555 traditional villages in China (the names are VillagesChina2555.kmz and VillagesChina2555.rar respectively). The dataset had eight data files, with the data volume of about 6.88 MB (compressed to 2 files, 416 KB).

4.2 Data Products

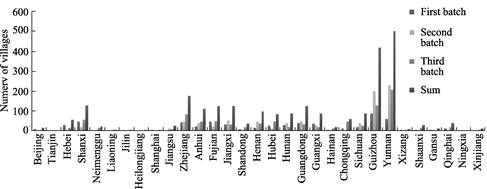

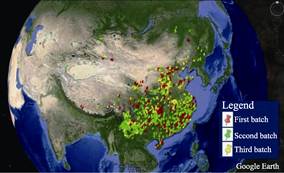

After counting the number of villages at the provincial and municipal levels, it can be seen that the number of villages in different regions was uneven. The percent of villages in Yunnan and Guizhou was more than 10%, but the number of villages in Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, and Shanghai was less than 10. The number of villages in Liaoning and Jilin in the first batch was zero, and it is zero in Tianjin, Liaoning, Shanghai, and Hainan in the second batch. Tianjin, Shanghai and Ningxia also had no village in the third batch (Figure 5). The distribution of 2,555 villages nationwide is shown in Figure 6 (Google Earth).

The position adjustment of the village: the related paper[6] used the Baidu map to match the position in the previous period. It needs to be adjusted due to the difference of the Baidu map itself and the difference in the location of the Google Earth. First, 100 villages’ positions were proofed or fine-tuned, and it can be seen that more than 90% of the locations have some misalignments. When the attribute tables are linked together, the coordinates will be misplaced. For example, when opening a file in Google Earth, there will be a possibility that village points fall into the cultivated land, so we need to fine-tune their location and then switch to .shp format for storage.

Figure 5 Distribution of traditional villages in various provinces and cities of China

5 Discussion and Conclusion

The village point coordinates of the dataset were extracted by using the Baidu map and the Google Earth image. Through the coordinate extraction, the village list can now display the spatial distribution. The dataset can be used to grasp the spatial relationship of Chinese traditional villages and provide an important basis for the study of the Geographical features. The village coordinates are extracted by three kinds of datasets. The number of villages whose coordinates could be directly checked or picked up from the geometric center

accounted for 75% of the total. In addition, the overlay of village point on Google Earth showed that the spatial distribution of the Chinese traditional villages varied greatly, with some areas having no such villages. Because the villages are restricted by different geographical conditions, it has some limitations to determine the number of villages mainly by administrative

division.

|

Figure 6 Spatial distribution of 2,555 Chinese traditional villages over Google Earth images (first 3 batches)

|

Author Contributions

Yu, L. designed the dataset development and wrote the data paper; Liu, J. guided the processing of key data; Cao, Q. Y., Ding, Y.Q, Liao, Q. X., Tang, M. J., and Fu, M. re-collected and processed the dataset.

Acknowledgements

Undergraduates Yan, Y., Zhao, Y. T., Feng, X., Lei, Y., and Yuan, X. Y. participated in the extraction of previous village data. We are deeply grateful for their contributions.

References

[1] Chen, J. Q., Zhang, Y. F., Chen, M. J. Review of Chinese ancient village research [J]. Journal of Anhui Agricultural Sciences, 2008, 36(23): 10103-10105.

[2] Wu, Q. X., Han, L. F., Zhu, L. Q., et al. Layout analyses of Wuyuan ancient villages [J]. Planners, 2010, 26(4): 84-89.

[3] Yan, S. Analysis of the characteristic and causes of Chinese traditional villages’ distribution [J]. Journal of Dali University, 2014, 13(9): 25-29.

[4] Liu, D. J., Hu, J., Chen, J. Z., et al. The study of spatial distribution pattern of traditional villages in China [J]. China Population, Resources and Environment, 2014, 24(4): 157-162.

[5] Kang, J. Y., Zhang, J. H., Hu, H., et al. Analysis on the spatial distribution characteristics of Chinese traditional villages [J]. Progress in Geography, 2016, 35(7): 839-850.

[6] Yu, L., Meng, X. L. Extracting spatial distribution patterns of the traditional villages based on geographical grid classification method [J]. Progress in Geography, 2016, 35(11): 1388-1396.

[7] Zhou, C. H., Ou, Y., Ma, T. Progresses of geographical grid systems researches [J]. Progress in Geography, 2009, 28(5): 657-662.

[8] Yao, Y. H., Zhang, B. P., Luo, Y., et al. The application of grid computing method to the research of spatial pattern: An analysis of karst landscape pattern in Guizhou [J]. Geo-information Science, 2006, 8(1): 73-78.

[9] Goodchild, M. F., Guo, H., Annoni, A., et al. Next-generation digital earth [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2012, 109(28): 11088-11094.

[10] Blog of Gudao: Shuiyu Village, Nanxun Township, Fangshan, Beijing [OL]. http://blog.sina.com.cn/u/ 3253570163.

[11] WLXWW: Litun Village, Shitang Town, Wenling City, Taizhou City [OL]. http://wlnews.zjo.com.cn/wlrb/ system/.

[12] Yu, L., Liu, J., Ding, Y. Q., et al. The spatial distribution dataset of 2555 Chinese traditional villages [DB/OL]. Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository, 2018. DOI: 10.3974/geodb. 2018.04.06.V1.

[13] GCdataPR Editorial Office. GCdataPR data sharing policy [OL]. DOI: 10.3974/dp.policy.2014.05 (Updated 2017).